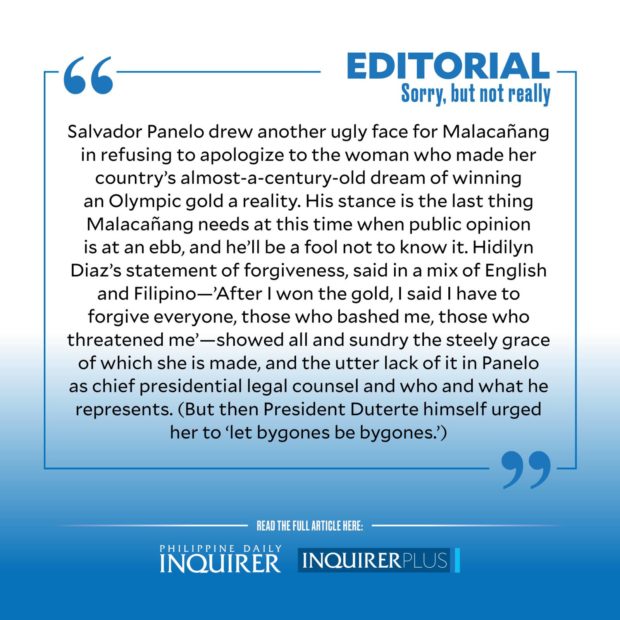

Salvador Panelo drew another ugly face for Malacañang in refusing to apologize to the woman who made her country’s almost-a-century-old dream of winning an Olympic gold a reality. His stance is the last thing Malacañang needs at this time when public opinion is at an ebb, and he’ll be a fool not to know it. Hidilyn Diaz’s statement of forgiveness, said in a mix of English and Filipino—“After I won the gold, I said I have to forgive everyone, those who bashed me, those who threatened me”—showed all and sundry the steely grace of which she is made, and the utter lack of it in Panelo as chief presidential legal counsel and who and what he represents. (But then President Duterte himself urged her to “let bygones be bygones.”)

Panelo even made light of the champion weightlifter’s pain, calling it “misplaced.” He said he was not sorry for the inclusion in 2019 of her name in an alleged plot to oust the President, sorry only that she felt “hurt.” It was at a formal briefing in the closing days of the campaign for the 2019 midterm elections that he presented to reporters a white cartolina on which was sketched a “matrix” of persons supposedly involved in the plot: critics of the government, opposition figures, journalists, and Hidilyn Diaz. He and Communications Secretary Martin Andanar were dressed to the nines when they put up the diagram; it was not an interview on the fly.

But, according to Panelo, he made the presentation in May 2019 on the President’s say-so and on the regular assumption that intel had properly vetted it. That it was a wrong assumption—Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana subsequently said there was no credible oust-Duterte plot then—was of no moment to him.

Along with the others accused without evidence, Hidilyn Diaz had denied involvement in any such plot. She was shocked and frightened at what the allegation could mean to her security as well as that of her parents and other family members in Zamboanga City. She said her mother was reduced to tears by journalists’ questions about the “matrix,” something her mother could not understand.

The allegation surfaced shortly after she overcame personal embarrassment and made a public cry for help: that she was in dire straits—“Hirap na hirap na ako”—and needed financial support to push her dream of an Olympic gold for the motherland. Is it okay to seek sponsorships from private companies? she asked plaintively. But her plea for support was perceived as criticism of the government; the intense online bashing and destabilizer-tagging that ensued were part of the burden she endured on the way to the Tokyo Olympics. Yet she was no mere moocher, or politician still to properly account for funds used in the 2019 Southeast Asian Games. She has done her country proud in other remarkable ways—as silver-medal winner at the Rio de Janeiro Olympics in 2016, and as top-prize winner at the 2018 Asian Games in Jakarta.

Two critical points stand out from Hidilyn Diaz’s gold-medal finish in Tokyo. One is the lack of government backing for Filipino athletes, a problem with which they have long had to grapple. There is hardly a local sports program to speak of. Many athletes training for international competitions do so under the aegis of private corporations or, quite rarely, on family support. Amid the collective happiness that her Olympic triumph brought, Hidilyn Diaz has called for more attention and support for her fellow athletes, having fully known that, apart from Team HD, it takes a village to produce a strong, motivated, and determined champion.

The other critical point is the seeming pattern in branding critics of the government, including, in her case, a star athlete forced to publicly beg the private sector for assistance, as destabilizers and enemies of the state. Many thus branded, ordinary citizens who experience and struggle against injustice, have lost not only livelihoods but also their lives. Today’s darling, into whose bandwagon sly pols are now trying to climb, is fortunate to have been able to turn things around. Still, her mother is fearful for her safety.

But Malacañang will not apologize for that grievous injury inflicted on Hidilyn Diaz and her family. It’s like a warrant cavalierly issued by some court for the arrest of a dissenter, which another court would then find wanting and render void—with not so much as a twinge of remorse or indignation from the government. It represents the state’s brute power.