Who remembers Romeo Jalosjos Sr.? In 1997, the then congressman from Zamboanga del Norte was sentenced to life in prison for the rape of an 11-year-old. Despite his incarceration, Jalosjos managed to win in two subsequent elections while still behind bars, and then in 2009 was released and allowed to return to his family after receiving a commutation from former president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo.

Today, as reported in the Mindanao-based Newsline last March, Jalosjos, now in his 80s, wears the hat of a successful businessman and a political player, throwing his full support behind the putative candidacy for president of Davao City mayor Sara Duterte. But his past may yet haunt him, as the debate swirls around the need for the Philippines to increase the age of sexual consent from below 12 years old, the lowest in Asia and among the lowest in the world, to below 16 years.

Bills increasing the penalty for statutory rape are still pending in the legislature. The House of Representatives passed its version of the bill late last year, while the Senate version, although passed at the committee level, has yet to hurdle the plenary vote. It will then have to go through a bicameral conference committee before being passed into law.

But time is running out. Already, the political class is all agog over next year’s elections. Once the deadline for the filing of candidacies in October lapses, one can rightly surmise that all work on other matters, including the need to increase the age of sexual consent, will come to a screeching halt. Then work on a new law will have to begin from scratch.

“Every single day that the passage of this important bill is delayed is another day of exposing Filipino children to the dangers of the archaic provisions of the Revised Penal Code on statutory rape,” says Child Rights Network convenor Romeo Dongeto.

So urgent is the need that the heads of different United Nations agencies in the country have called on Congress to prioritize the pending bill’s passage.

In 2015, said the UN agencies, the first National Baseline Study on Violence Against Children, led by the Council for the Welfare of Children, revealed that one in every five children here reported experiencing sexual violence, while one in 25 experienced “forced consummated sex” during childhood. Also revealed in the study: Perpetrators are often family members, and more boys than girls reported experiencing sexual violence.

The measures proposed by the UN agencies and child rights groups include: “increasing the age to determine statutory rape from below 12 to below 16; equalizing protection for victims of rape regardless of gender; adopting the ‘close in age exemption,’ which serves to avoid criminalizing adolescents of similar ages for factually consensual and non-exploitative sexual activity; and removal of marriage as forgiveness exemption, where the perpetrator is freed of legal responsibility if the perpetrator marries the victim.”

“Sexual violence results in severe physical, psychological and social harm for children,” the UN agencies pointed out. “Victims experience an increased risk of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, pain, illness, unwanted pregnancy, social isolation and psychological trauma. Some victims may resort to risky behaviors like substance abuse to cope with trauma.”

In a report in CNN, reporter Jessie Yeung said victims’ advocates also argue that “the low age of consent contributes to what international rights organizations have described as high levels of sex trafficking and teenage pregnancy, compounded by gaps in the enforcement of existing laws.”

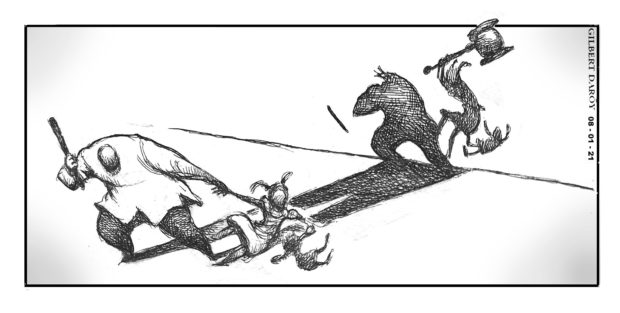

There is another argument for raising the age of sexual consent, per child rights activists: Children 12 years and below “are incapable of giving consent, and less likely to know how to call for help.” The present law protects predators because “they can claim victims consentedʍand children as young as 12 can often be coerced or threatened into silence.”

Why has the threshold of 12 years old persisted despite years of research and advocacy and the passage of the progressive anti-rape law and similar laws regarding children’s rights?

An official of Unicef Philippines cited “the lack of education and understanding among lawmakers and the general public of concepts like children’s cognitive development and the ability to give informed consent.” Some lawmakers have also resisted the call to amend the law on statutory rape, arguing that there are already existing laws against child abuse. “The answer has always been, ‘Well, because we already have laws about this,’” said Dr. Bernadette Madrid, executive director of the Child Protection Network Foundation.

That oblivious mindset needs to change, to ensure that Filipino children are better protected from harm.