In his heyday as first gentleman, Jose Miguel “Mike” Arroyo filed at least 40 criminal libel suits against journalists on allegations of acts of corruption and of aiding and abetting his wife, then President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, in rigging the 2004 presidential election. The threat of arrest and imprisonment hung over the heads of those sued and indeed of their comrades in the profession; it didn’t help that the killing of journalists was also occurring at a frightening rate in the countryside (the murder in March 2005 of Marlene Esperat, who was shot dead in front of her then 10-year-old son by a gunman who had casually walked into her home, was particularly, chillingly, brutal).

In May 2007, “grateful for surviving a delicate open-heart surgery with a very low survival rate,” Mike Arroyo sought peace and reconciliation with those he had haled to court and withdrew all of the libel suits. But before then, in December 2006, journalists and news organizations filed a class action suit with the Makati Regional Trial Court against the first gentleman, claiming abuse of power. They sought damages of P12.5 million, the money to go to a press freedom fund if the suit succeeds. The matter was last heard about in May 2010, with the Supreme Court upholding the Court of Appeals (CA) in rejecting the Arroyo camp’s petition to throw out the class suit.

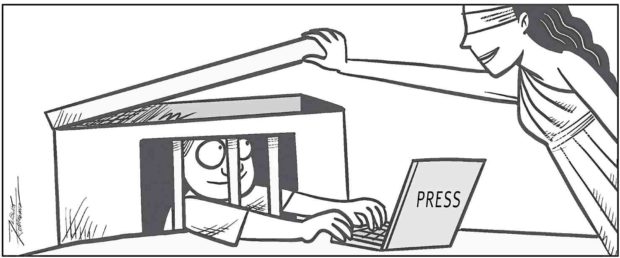

This flashback provides ample context to a recent ruling by the Supreme Court that gives journalists a leg up in their continuing struggle to decriminalize libel. In the ruling dated Jan. 11 but released to the media only on June 29, the high court’s Third Division reversed a Pasay City court’s libel conviction of broadcast personality Raffy Tulfo for a tabloid column written 22 years ago. It said the constitutionality of the definition of libel as a criminal offense was “doubtful,” and cited the press’ “vital role” in checking government abuse.

“In libel, the kinds of speech actually deterred are more valuable than the state interest the law against libel protects,” the Supreme Court said in its ruling that also cleared Allen Macasaet and Nicolas Quijano, then publisher and managing editor, respectively, of the tabloid Abante Tonite.

Tulfo had written about the extortion and other illegal activities of lawyer Carlos So of the Bureau of Customs. So sued him and the others of 14 counts of libel; the Pasay court convicted them of the crime and was upheld by the CA in 2006. On their motion for reconsideration, the CA in 2009 amended its decision and acquitted them of 8 of the 14 counts. Tulfo et al. raised their case to the Supreme Court.

Said the high court in its ruling: “Our libel laws must not be broadly construed as to deter comments on public affairs and the conduct of public officials. Such comments are made in the exercise of the fundamental right to freedom of expression and of the press.”

More: “[W]ithout a vigilant press, the government’s mistakes would go unnoticed, their abuses unexposed and their wrongdoings uncorrected.”

The Supreme Court said the libel cases it had handled generally involved “notable personalities as parties, highlighting a propensity for the powerful and influential to use the advantages of criminal libel to silence their critics.” It said civil, rather than criminal, charges could be a better legal recourse for anyone seeking protection against defamation.

The high court’s remark on power and influence being brought to bear on government critics calls to mind what the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists said about the libel suits filed by Mike Arroyo: “a clear sign that those in power wanted to use the [Philippines’] legal system to harass journalists who dared challenge the Arroyo administration.”

The ruling shines a bright light on the current dark landscape in which government critics constantly risk being at the receiving end of official retaliation. And in Zambales, another legal development buoys hope: the rebuff by provincial prosecutor Jose Theodoro Santos of the National Bureau of Investigation’s third attempt to file a sedition complaint against high school teacher Ronnel Mas, for his supposed tweet offering P50 million to anyone who would kill President Duterte.

Santos cited “lack of probable cause” and “insufficiency of evidence” in explaining the dismissal of the complaint. Last year, “lapses” in Mas’ warrantless arrest led Olongapo Judge Richard Paradeza to reject the NBI’s initial charges. These displays of judicial independence show that the constitutional rights of ordinary people can conceivably prevail over weaponized law.