Entrepreneurs, investors, and the business community will remember the late president Benigno Aquino III as the chief executive who steered the Philippine economy through six years of consistently high economic growth, finally allowing the country to shed its label as “the sick man of Asia.”

During his presidency, gross domestic product (GDP) expanded by an average of 6.2 percent a year — the fastest pace since the1970s. The 7.8 percent registered in the first quarter of 2013 was unprecedented, outpacing Indonesia and even China for the same period. This was accomplished at a time when many economies around the world were struggling from the lingering effects of a global recession triggered by the subprime financial crisis in the United States in 2008-2010.

Economists agree that the Aquino administration was able to put the government’s finances in order mainly through a transparent budgeting process that led to lower public borrowings and, in turn, smaller budget deficits. And there were very few new taxes imposed during his administration.

The fruit of this is the coveted investment-grade rating given by global debt watchers such as Moody’s and Standard and Poor’s in 2013, the first-ever such rating received by the Philippines. This badge of good housekeeping, so to speak, had the effect of lowering the borrowing cost of both the government and the private sector, as the credit rating gave confidence to foreign lenders about the capacity of the Philippines to honor its obligations. The interest rates carried by Philippine borrowings during Aquino’s term fell to 4 percent from the previous administration’s 12 percent.

A number of game-changing laws were also enacted during the Aquino presidency, led by the controversial “sin” tax law that raised imposts on alcoholic products and cigarettes. It was one piece of legislation that boosted government coffers. The universal coverage of health insurance enjoyed by Filipinos today is largely financed by such taxes.

Robust growth allowed the Aquino administration to lift more than 7 million people out of poverty by expanding the Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) program, described by the World Bank as one of the best in the world in targeting the most disadvantaged sectors of society. An estimated 4.6 million families benefited from the CCT, which has been continued by the Duterte administration through the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino program or 4Ps.

One clear reflection of Aquino’s economic performance was the consistent rise in the Philippines’ ranking in the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) Global Competitiveness Report, which measures investment attractiveness, ease of doing business, and other indicators of a nation’s worthiness as an investment destination. In 2011, the Philippines jumped 10 notches to 75th among 144 countries in competitiveness. In 2015, the Philippines ranked 47th, the fifth highest-ranking among countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean). From 2010 to 2015, the Philippines was able to climb 38 spots in global competitiveness rankings.

The Philippines’ ranking in the Control of Corruption category of the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), on the other hand, was consistently in the top 50 out of 213 countries worldwide. Another global corruption yardstick, Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index, also saw the Philippines’ standing move up several notches from 2010 to 2015.

The country’s economic high translated to public optimism. “Public morale was very high under PNoy,” pollster Mahar Mangahas of Social Weather Stations wrote in his column in this paper last Saturday. “The surplus of economic optimists over pessimists was +30. This indicator, which started in 1998, is often negative; it had been positive only 3 times in Estrada’s time and only 6 times in Arroyo’s 9-year period. In PNoy’s time, however, it was always positive, and Very High 15 times in 22 surveys.”

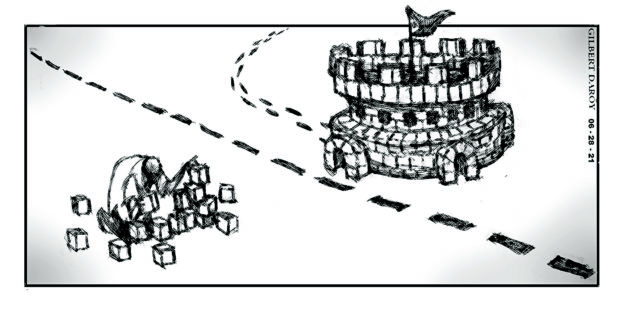

At the end of his presidency in 2016, Aquino left the country a stable, thriving economy (“the fastest among 11 Asian economies during that year’s first three months,” per an Inquirer report). While the succeeding Duterte administration maintained the high-growth trend through the first half of its term, the global COVID-19 pandemic that struck last year has now negated much of the economic gains. Recession took hold of the economy, unemployment swelled as a result, and millions of families were pushed back into poverty. Government finances have weakened as the economic difficulties curbed tax revenues and the health crisis caused unexpected expenses that the administration has had to cover with borrowings.