Unqualified condemnation

What could Kieth Absalon have become had his life not been snuffed out on June 6 in Barangay Anas in Masbate City? He is buried now, “finis” so abruptly stamped on his 21-year life, at that point when, in an ideal world, hopes and dreams are just beginning to be realized and promise to open new doors, each more thrilling than the last.

When he went out biking on that morning with his cousin Nolven Absalon, 40, and the latter’s 16-year-old son, along with other relatives, Kieth was in the thick of training for a biking race in Masbate in July. Who knew but that this strapping, constantly smiling midfielder of the Far Eastern University men’s football team would have easily crunched, even topped, the race? His experience would have made it possible, having been named most valuable player of the University Athletic Association of the Philippines in 2016 and seen action in the 2018 Asean Football Federation Championships in Indonesia as part of the Under-19 Philippine team.

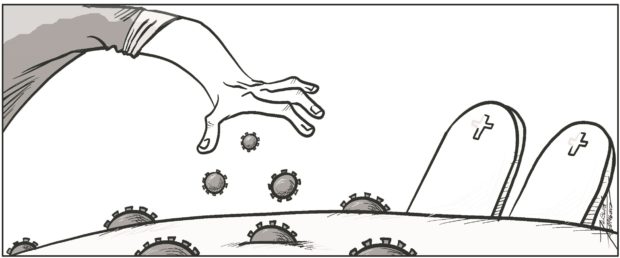

Article continues after this advertisementBut all that is now a painful memory for those who love this young man. An improvised explosive device planted by and command-detonated by New People’s Army (NPA) fighters killed him and his cousin Nolven—

a father of four and himself a great loss—and injured Nolven’s son. The NPA, armed wing of the Communist Party of the Philippines, has since taken responsibility and expressed “deep remorse” for the crime. Still the family’s grief cannot be eased. The death certificates indicate that the cousins died due, not only to “blast injuries” but also to “gunshot wounds.”

The tragedy is exacerbated by the fact that, but for some perverse quirk, it could not have occurred at all. Early on, Kieth’s father Nathaniel Absalon said his son and nephew had been “mistakenly identified as military” by the insurgents. Maj. Maria Luisa Calubaquib, spokesperson of the Bicol Regional Police, said: “This might be a mere accident. They ran into the IED recklessly planted [by NPA rebels]. Their targets [were] probably the uniformed personnel.” The NPA itself said as much; Raymundo Buenfuerza, spokesperson of the Romulo Jallores Command operating in Bicol, said the detonation of the land mine was a mistake for which the rebel force “ask[s] for forgiveness [from] the family and the public.”

Article continues after this advertisementThis is why the killing of Kieth and Nolven Absalon demands unqualified condemnation. The use of land mines is an act so deliberate, so final, that any claim of an accident or a mistake, even if true, becomes inconsequential in the face of the lives instantly lost or — a fate deemed worse than death — grievously maimed. Kieth’s mother Vilma Absalon lamented how he was lovingly raised and how he strove to attain his dreams, “and he would die just like that.”

The law is clear: Person-activated land mines are prohibited under the 1997 Ottawa Treaty (or the Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction). Command-detonated land mines directed at civilians are banned under the 1996 Amended Protocol 2 of the 1980 Conventional Weapons Convention.

And international humanitarian law (IHL) forbids it. “Not only,” said Commission on Human Rights spokesperson Jacqueline de Guia, “do [land mines] cause exceptionally severe injuries, suffering and death, [they] also fail to distinguish between civilians and combatants, such as what happened in this case.”

Quite predictably, the killing of the Absalons has led to more killings in Barangay Anas. Days after the explosion, Major Calubaquib reported an alleged firefight between at least 30 suspected insurgents and a

police-military team said to be serving an arrest warrant on murder suspect Arnold Rosero. The bodies of three alleged rebels were found 15 minutes after the supposed firefight. Per the authorities, it was insurgents led by Rosero who planted and detonated the IED on the route taken by the Absalons. But according to the families of the dead “rebels,” they were mere farmers—echoes of many other cries protesting perceived state terror.

The long-running insurgency that drew shape from impoverishment and society’s ever-sharp inequities and the government’s relentless mission to crush it have made orphans of many children and drenched the countryside with blood. Activist lawmakers in the House urge the bereaved Absalons to lodge a complaint at the peace talks’ Joint Monitoring Committee as a reminder to all signatories of the Comprehensive Agreement on Respect for Human Rights and IHL to abide by the laws of war. It’s a reasonable call aimed at preventing the Philippines from descending further into scorched earth.