Curbing wildlife trafficking

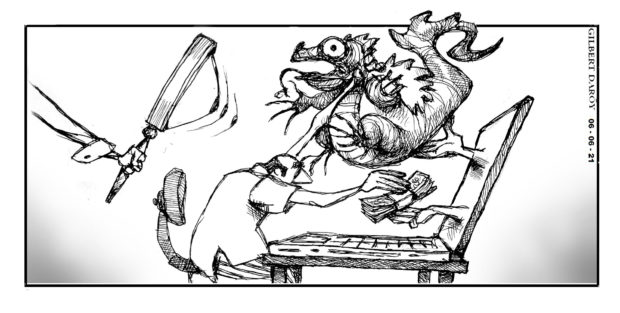

Editorial cartoon

The coronavirus may have slowed down businesses, including the illegal wildlife trade, but it has not totally stopped smugglers from flouting regulations.

Instead, they have innovated ways to continue conducting their illegal business through the use of modern technology — only highlighting the need to amend and upgrade the country’s 20-year-old wildlife conservation and protection law and introduce stiffer penalties.

From April to June last year, despite the ongoing pandemic and government-imposed lockdowns, the Wildlife Resources Division (WRD) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) noted a spike in reports of illegal wildlife trade, which was valued at P50 billion annually before the pandemic.

The reason? Smugglers had moved most of their business transactions online, to social media platforms like Facebook or Instagram.

Among the widely traded animals were monitor lizards (locally known as “bayawak”).

Wildlife trade monitoring network TRAFFIC noted that two-thirds of advertisements on Facebook from 2017 to 2020 for the reptiles came from the Philippines, where it is illegal to collect and trade them for commercial purposes.

The monitor lizards were being traded as exotic pets in the United States and European markets, or sold for their skin to the leather industry, or their meat for human consumption.

TRAFFIC also reported that the Philippine forest turtle, a rare and critically endangered species, was another highly coveted animal in online trading sites in China and in the Philippines.

In 2018, even before the migration of illegal wildlife traders online, tech and social media companies had formed the Global Coalition to End Wildlife Trafficking Online.

Among the more than 30 members are Facebook, Google, and Twitter; these companies share information with wildlife experts, monitor keyword searches, and tap volunteers called “cyber spotters” who report illegal wildlife trading.

As of March 2020, according to the coalition, more than three million listings for endangered species had been taken down from the internet. The illegal traders, however, just move to other platforms like WhatsApp, Telegram, or WeChat, which are harder to monitor and where they can make one-on-one deals with clients.

“Online wildlife trafficking has escalated the illegal trade, with millions of online users potentially having direct access to illegal suppliers all over the world with just a few clicks. This makes it more difficult for authorities to detect and to take effective action,” said Asean Centre for Biodiversity executive director Theresa Mundita S. Lim in a news report.

National laws have to keep up with the trend, she urged, noting that existing regulations may limit enforcers from going after illegal traders online. Advocates have also noted that penalties are not harsh enough to deter wildlife smugglers.

Under Republic Act No. 9147 or the Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act, penalties depend on the violation committed and the conservation status of the wildlife: six months to one-year imprisonment and/or P50,000 to P100,000 fine for the transport of wildlife; and from two to four years of imprisonment and/or fine of P30,000 to P300,000 for hunting wildlife, and P5,000 to P300,000 for their trading.

The stiffer penalties are reserved for those found guilty of killing critically endangered wildlife: a jail term of six years and one day to 12 years and/or payment of fine ranging from P100,000 to P1 million. First-time violators are granted probation and allowed bail.

Environment Secretary Roy Cimatu already said last year that there is a need to amend RA 9147 “to include a mandatory minimum jail term of six years for those found guilty of the criminal acts defined under the law. This is to make sure that convicted offenders will be able to serve their sentence and will not be eligible for probation.”

Theresa Tenazas, head of the DENR’s WRD, said the penalties in RA 9147 no longer serve as a deterrent: “The landscape is changing—we live in an online era and we can’t keep up with a 20-year-old law.”

At least two bills seeking to amend RA 9147 have been filed at the Senate, while the House of Representatives committee on appropriations approved last May a consolidated bill that will impose stiffer penalties on violators: a prison term of one month and one day, plus a fine of P20,000 for minor infractions; and imprisonment of 12 years and one day to 20 years, and a fine of P200,000 to P2 million for killing critically endangered wildlife.

The amended law will not end illegal wildlife trade, said lawyer Edward Lorenzo, policy and governance adviser of Conservation International Philippines, but it can help minimize the problem: “What we want is our enforcers to be prepared, so that when the world opens again and the illegal trade comes back, at least they are more ready.”