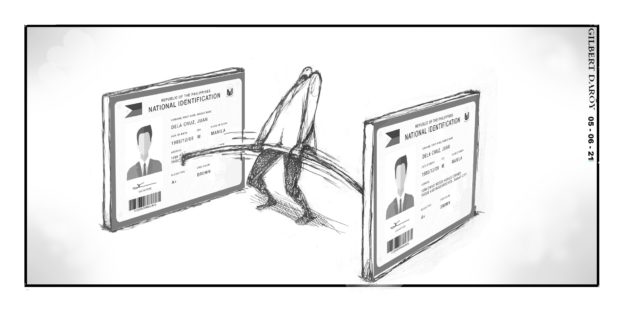

Editorial cartoon

Ironic is an understatement to describe the hyped launch last week of the online registration for the Philippine Identification System (PhilSys), which was supposed to “accelerate our transition into a digital economy”ʍbut which ended up as a big dud due to technical glitches.

Per National Economic and Development Authority Secretary Karl Kendrick Chua, the dedicated registration portal was designed to process only 16,000 simultaneous users per minute, with some leeway to go up to 35,000. But the portal run by Neda attached agency Philippine Statistics Authority attracted some 46,000 users in the first few minutes alone, overwhelming the system and making it unable to send the one-time passwords needed to proceed with the registration.

“Ito ay three times the capacity. Ang nangyari po, bumagal po ’yong website at maraming hindi na-serve, kasi mayroon po tayong mga slowness or downtime,” an apologetic Chua said. He sought to assure the public that Neda was already in discussions with experts on how to improve the system. “Since this is a pilot program, we will learn—make sure to learn from our experience,” he added.

In his Monday address, President Duterte downplayed the failed launch and even commended Chua for the kickoff of PhilSys’ online registration.

However, serious doubts over the government’s capability to handle massive digitalization programs are not so easily brushed off, considering the Philippines’ history of shoddily run online government programs and, worse, major data breaches that have undermined public confidence and heightened Filipinos’ concerns over the safety of their personal data in government hands.

According to the 2020 Unisys Security Index released in August last year, 9 in 10 Filipinos are worried about identity theft, undoubtedly stoked by data breaches that have long hounded government websites. The US International Trade Administration noted last month that “with few data protection mechanisms” despite its robust social media-savvy population, the Philippines is “extremely vulnerable to cyber-attacks and incidents.” One 2019 study in fact ranked the Philippines as the fifth country most likely to be attacked, following Algeria, Nepal, Albania, and Djibouti.

In 2016, the country suffered its most significant data leak after the hacking of millions of voter data registered with the Commission on Elections just a month before the May general elections. Cybersecurity firm Trend Micro described the Comelec data breach as “the biggest government-related data breach in history.” Two hacking groups claimed responsibility for stealing some 50 million personal information of Filipinos, including “the fingerprints of 15.8 million individuals, and passport numbers and expiry dates of 1.3 million overseas voters.”

The Department of Information and Communications Technology (DICT) responded in 2017 with the launch of the National Cybersecurity Plan 2022, aimed at enhancing cybersecurity and the resilience of critical data infrastructure to ward off cybersecurity threats.

The robustness of the government’s online systems remains wanting, however, as serious attacks have continued.

In 2019, the database of the Armed Forces of the Philippines was hacked, exposing sensitive information on some 20,000 military personnel. Last December, the website of the Office of the Solicitor General was defaced; a London-based cybersecurity company said the OSG might also have been the subject of a more recent data breach. And in March, the National Bureau of Investigation confirmed that the government’s main website gov.ph was attacked by a group of “hacktivists” protesting the Duterte administration’s human rights record.

Given the administration’s target of registering 70 million individuals in PhilSys by the end of the yearʍthe aim is to do away with a patchwork of government-issued IDs and just have one single official ID issued to all citizensʍthe pressure is even greater on the frontline agencies to ensure not only that official websites and portals are functioning properly, but also, and more critically, that citizens’ personal data and transaction records are protected by reliably secure, well-guarded systems. Longstanding data privacy concerns were precisely what had hampered the implementation of the national ID system for years.

According to the PSA, more than 28 million Filipinos have already completed the first step of PhilSys registration, which involves the collection of basic personal data. Some 4.6 million have gone through step 2, the submission of biometric information. With such valuable data already in government hands, it is imperative for the DICT and other government agencies to step up, overcome the worst possible start to the online registration for PhilSys, and alleviate Filipinos’ fears over the perennially poor IT infrastructure of their government.