Addressing disasters, climate change, pandemics

The world’s strongest storm of the year—Supertyphoon “Rolly” (international name: Goni)—made landfall in the Philippines last Sunday. The typhoon, with winds in excess of 314 kph, is a stark reminder of nature’s destructive power almost 10 years after a similarly sized storm, “Yolanda” (Haiyan), caused 6,000 deaths and cost an estimated P676 billion to the country’s economy.

Early damage assessments after the latest typhoon, however, are an equally powerful reminder of the value of disaster preparedness. Since Supertyphoon Yolanda in 2013, almost P168 billion has been allotted to rehabilitation, i.e., resettlement, infrastructure, livelihood, and social services.

The National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council budget is used to fund disaster risk reduction activities and capital expenditures for pre-disaster operations, rehabilitation, and other related activities. Each line agency is allotted DRRM (disaster risk reduction and management) funds.

The Department of Social Welfare and Development, for example, was allotted almost P14 billion in 2012-2013, while the Office of Civil Defense had a total of almost P693 million as a quick response fund, to be used also for developing and implementing comprehensive national and local preparedness and response policies, plans, and systems and for equipping communities against the impact of disasters. This was according to a 2014 Commission on Audit report.

Disaster preparedness has repeatedly proven to be a smart investment to reduce the human and economic impact of disasters. However, investment in preparedness, particularly at the household level, continues to fall far short of needs, according to the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative’s (HHI) 2017 nationwide survey on household levels of preparedness for disaster in the Philippines.

The challenges brought by frequent disasters have been compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic, and point to the need for urgent adaptation and financing for disaster preparedness.

First, few, if any, preparedness and response plans are adapted for disasters occurring during a pandemic. While the pandemic is a unique challenge, the challenges associated with the spread of infectious diseases in the aftermath of disasters are not new, yet efforts to prepare for epidemics in such contexts remain insufficient. Numerous measures such as emergency shelter and emergency supply chains are not equipped to prevent the transmission of COVID-19, increasing the risk of transmission for individuals already made more vulnerable by the typhoon.

Major cities in the Philippines that are prone to flooding are also being impacted by COVID-19. Together with lockdowns implemented by the government, this makes humanitarian intervention programs harder to implement. As reported by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, in densely populated urban areas, people live on $3.10 or P150 per day, and people who go to evacuation centers are at risk of getting infected.

COVID-19 has exacerbated the conditions of already vulnerable populations. Disaster responders and public health professionals can at least adapt the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tips on how to lower the risk of infection in evacuation centers.

Second, disaster preparedness remains largely and logically focused on the immediate threat caused by specific events like typhoons. However, disaster preparedness and adaptation to climate change are closely linked and potentially mutually reinforcing, as HHI’s recent study in the Philippines showed. We, researchers at HHI, recommended that local humanitarian actors in the Philippines have more cohesive and reciprocal collaborations to further strengthen and sustain the country’s DRR and climate change adaptation system. There is an urgent need for an intervention framework and funding for policies and programs that link climate change adaptation and disaster preparedness.

As the Philippines turns to assessing damages and rebuilding after Rolly, it can derive lessons that would help firmly establish disaster preparedness as a core priority, while also moving on to the next challenges and adapting disaster preparedness and risk reduction strategies to address the transmission of infectious diseases and the long-term effects of climate change.

——————

Vincenzo Bollettino, PhD, is the director of the Resilient Communities Program at HHI.

Patrick Vinck, PhD, is research director of HHI, an assistant professor at the Harvard Medical School and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and lead investigator at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Lea Ivy Manzanero, MA, is a project lead at HHI implementing research of HHI’s Resilient Communities Program in the Philippines.

For more news about the novel coronavirus click here.

What you need to know about Coronavirus.

For more information on COVID-19, call the DOH Hotline: (02) 86517800 local 1149/1150.

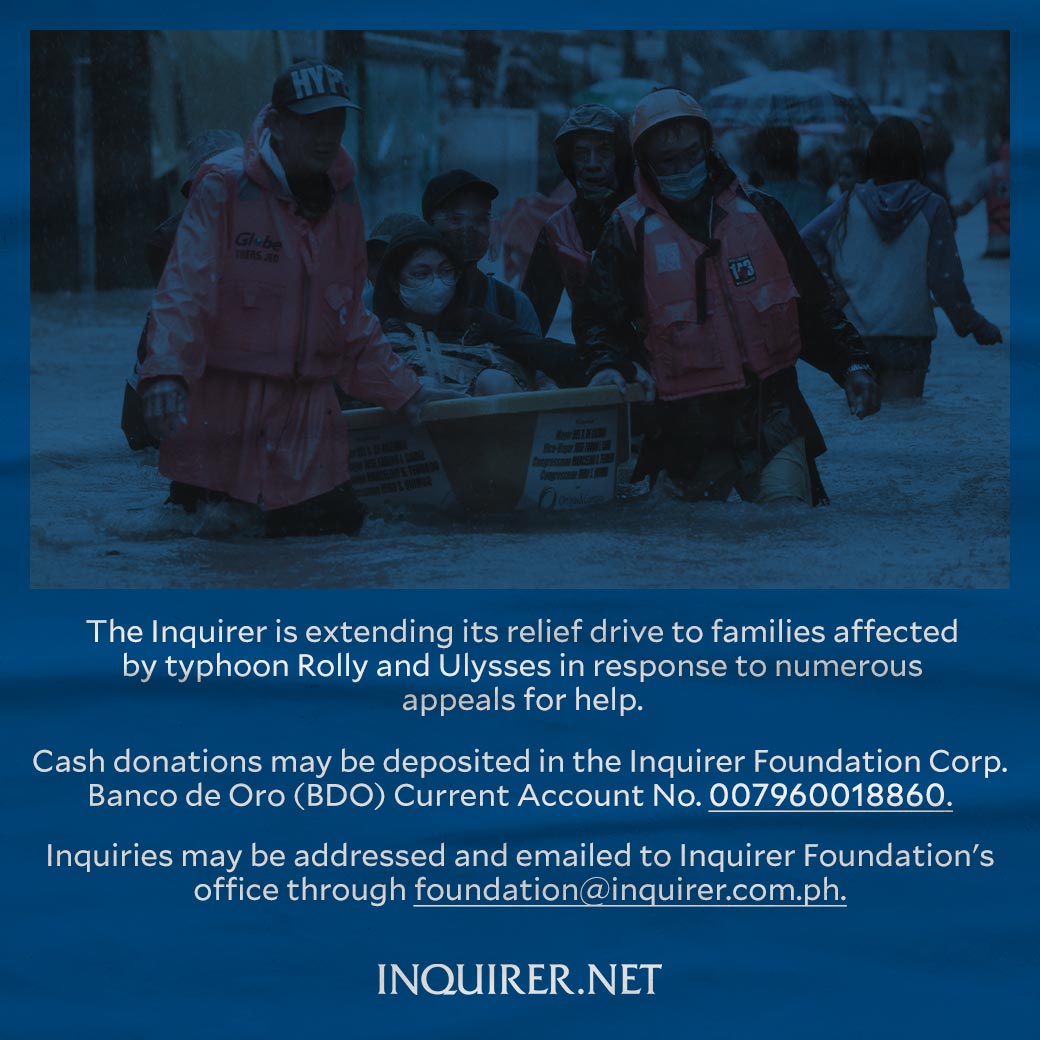

The Inquirer Foundation supports our healthcare frontliners and is still accepting cash donations to be deposited at Banco de Oro (BDO) current account #007960018860 or donate through PayMaya using this link.