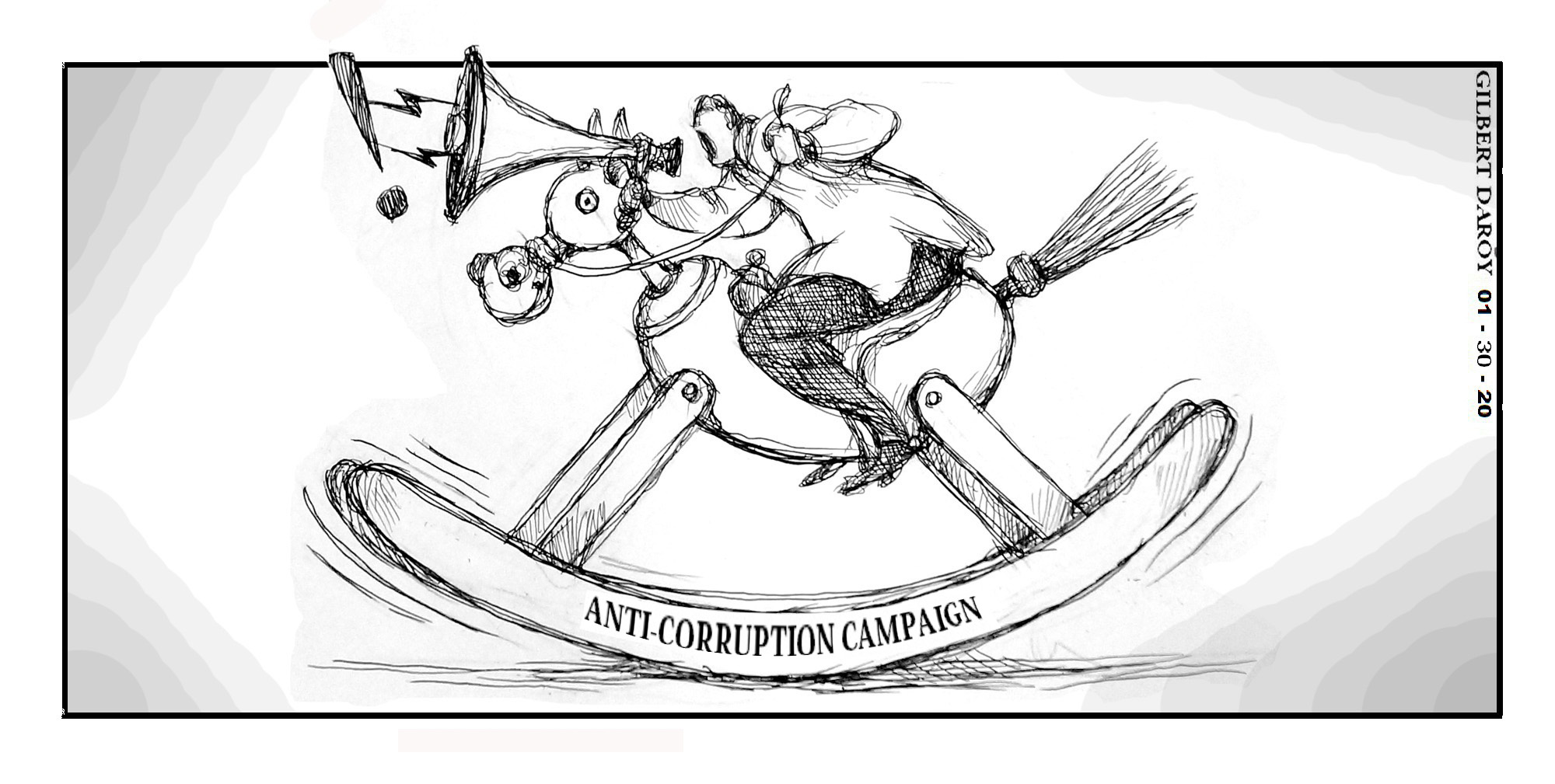

A President who vowed that “not even a whiff of corruption” would be tolerated in his term will not like what an international corruption watchdog has determined halfway through his tenure—that he’s failing at the promise big-time. According to the 2019 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) of Transparency International (TI), corruption in the Philippines is becoming worse, not easing up. In fact, the country now ranks among the most corrupt countries in the world. Out of 180 countries surveyed, the Philippines came in at number 113, several notches below its ranking in previous years: 14 slots down from 2018, 18 down from 2015, and its lowest ranking since 2012. Dirtier and dirtier the country’s affairs seem to be getting—or at least that’s the consensus among those polled by the TI, which reviews countries and territories through experts’ and businessmen’s perception of government corruption.

Malacañang, quick to take umbrage at any hint of criticism from international bodies, seemed among the least surprised at the results this time. Instead of bothering to work up an indignant denial, presidential spokesperson Salvador Panelo offered what sounded like a begrudging acknowledgment that the problem has indeed been hard to lick.

The President’s hands are “tied by the due process clause of the Constitution,” this “tedious process that demands evidence to get dishonest officials out of power,” Panelo claimed. “We’ve been fighting corruption and the President has been firing top government officials… (who) have been charged in the Ombudsman and in the courts.”

Yes, he has—but mostly those conveniently not close to him, who don’t have his ear, or are far down the governmental totem pole. The list of recycled favored officials, however, tell a different story. There’s former Customs chief Nicanor Faeldon, who “resigned” after a P6.4-billion shipment of crystal meth managed to slip into the country in 2017, but was then appointed to the Bureau of Corrections (where he also made a royal mess). Faeldon’s successor, Isidro Lapeña, was relieved as customs chief after allegations that some P11-billion worth of shabu were smuggled inside magnetic lifters during his watch—but was just as quickly ensconced at Tesda, the government agency for technical and vocational training. A presidential free pass for the two, while it was the lowly warehouse caretaker in the P6.4-billion drug smuggling case that was thrown in jail.

That selective anticorruption campaign blights as well the fate of government transactions that have all the earmarks of conflict of interest, such as the multimillion security services deals the company owned by Solicitor General Jose Calida’s wife Milagros had clinched with at least three government agencies. Rather than enforcing the Code of Ethics prohibiting conflict of interest among public officials, however, the President even defended Calida: “Why should I fire him? He’s good. And doesn’t he have a right to go into business?”

How about the anomalous advertising contract signed by former tourism secretary Wanda Tulfo Teo with her brothers worth some P60 million? The government has yet to recover the money—not that it’s even trying—or file charges against the Tulfos, all prominent Duterte partisans.

Most odiously, despite having been convicted of seven counts of graft, former first lady Imelda Marcos is yet to spend a single night in jail, and was even able to party at taxpayer expense at a recent tribute thrown by government officials in her honor.

In terms of transparency—the main criteria used by TI in assessing corruption in the countries it surveyed—the Duterte administration’s dim record accounts for the Philippines’ big drop in the ranking.

Underlining its signal failure to pass a promised Freedom of Information law and create a more transparent environment, the government has yet to release the 2018 statement of assets, liabilities and net worth (SALN) of the Chief Executive nearly 10 months since the April 30 deadline for its filing. Requests for Mr. Duterte’s SALN got ping-ponged between Malacañang and the Ombudsman, the mandated custodian of the SALNs. Alas, under Ombudsman Samuel Martires, whom Mr. Duterte appointed in August 2018, “the SALNs of senior officials are now kept under lock and key,” as the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism has noted, with Martires fashioning for himself a new job description as protector of the “privacy” of government officials.

The “whiff of corruption” the President had gone ballistic warning officials about has instead metastasized into the opposite—a stench of such magnitude that the collective olfactory nerves of government have now become too fatigued to even smell it at all.