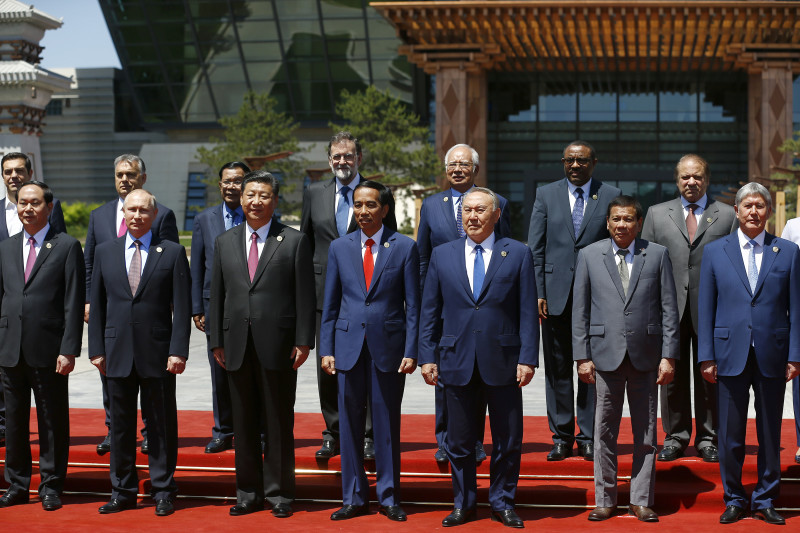

Chinese President Xi Jinping, third left in front, and other leaders pose for a family photo during the Belt and Road Forum at meeting’s venue on Yanqi Lake just outside Beijing, Monday, May 15, 2017. (Damir Sagolj/Pool Photo via AP)

The Belt and Road Forum in Beijing over the weekend was yet another coming-out party for the new superpower. China’s impressive hosting of the 2008 Olympics had heralded its arrival on the world stage. Its climate change diplomacy that helped lead to the Paris Agreement of 2015 has cemented its leadership in global issues. Last weekend’s summit, attended by 28 heads of state or government, sealed its position as an economic power.

The Belt and Road Initiative (the current form of what Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013 first called the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Route) is an ambitious undertaking: Essentially a massive infrastructure-development plan, it involves some 70 countries and entails as much as $5 trillion in spending. Most of the money will come from China. At the forum, Xi announced that an additional $113 billion in funding would be made available.

Striding confidently into the leadership space abandoned by the isolationist Donald Trump, Xi used his opening speech to position China as the new hub of the global economy. “We will build an open platform, defend and develop an open world economy, jointly create an environment good for opening-up and development, and push for a just, reasonable and transparent international trade and investment system so that production materials can circulate in an orderly way, be allocated with high efficiency and markets are deeply integrated.”

Among those who joined the forum were President Duterte and other leaders from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, Presidents Vladimir Putin of Russia and Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey, and the heads of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

The scale of ambition driving Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative is unprecedented. Part of the reason lies in the way the initiative has been packaged. A 2016 PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) study noted: “Some of the core elements of the B&R initiative (such as a focus on infrastructure investments in underdeveloped Western China and Central Asia) are far from new and long predate the public announcements in 2013. B&R, however, bundles all ongoing and planned efforts—such as the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Corridor (BCIM)—under one unifying framework.”

In other words, parts of the Chinese infrastructure investment spree antedated even Xi’s rise to power. But the “unifying framework” is important, because it symbolizes, and enables, Beijing’s priorities. The PwC study again: “Initially covering only the development of Western China and specifically the interior state of Xinjiang, the B&R initiative in its full extent is now reflecting China’s outbound focus in three directions: West (West China, Central Asia, the Middle East and Europe), East (Southeast Asia), and South (South Asia and Africa). For various reasons, Eurasia (because of its proximity to Western China, abundance of natural resources and need for greater regional stability) and Southeast Asia (due to the importance of its trade with China) will be given priority.”

There is opportunity for the Philippines, and for Philippine businesses.

But caveat emptor. China has not yet fully emerged from its totalitarian communist past. While Xi is focused on modernizing China’s main institutions, statistical data in China and about China remain suspect. While Xi is spending significant political capital cracking down on corruption, state-owned enterprises continue to dominate the Chinese economy. And while Xi has returned again and again to the theme of regional cooperation, China’s old principle of a “harmonious rise” in the world has been junked in favor of an aggressive posture in the South China Sea.

There are also disturbing tales from projects in Africa or Asia, or about China’s deepening debt. The moral of these stories may well be: Proceed, but with caution. Lots of it.