Ways to fix ‘sick book’ problem

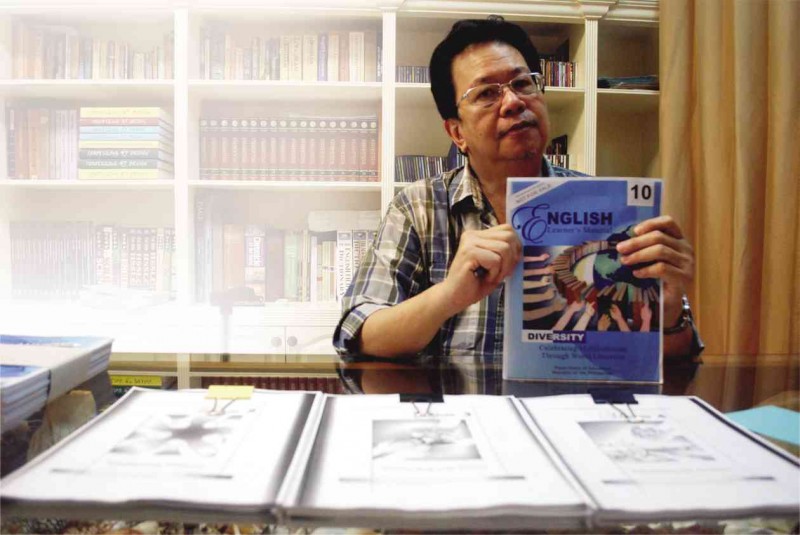

Book error spotter Marian School academic supervisor Antonio Calipjo Go shows the textbook where he found 1,300 errors. ARNOLD ALMACEN

The 1,300 errors that “sick book” crusader Antonio Calipjo Go found in a book that the Department of Education (DepEd) published recently hogged the headlines. The book is a learner’s material for Grade 10 students.

DepEd said the book was only a first draft but Go insisted the draft book was still anomalous. In a press statement, DepEd pointed out that developing the learning materials and teaching guides “involves several stages of drafting, editing and validation, as well as various consultations with content writers, reviewers and editors before printing.” That is the correct process. But was this process followed?

Every citizen’s concern

Book publishing for teaching and learning is every citizen’s concern. So, what were those 1,300 errors? A combination of factual errors, grammatical errors, misspelling and typos.

A textbook normally contains a lot of text and a few pictures or none at all. Ordinarily, when manuscripts are being prepared, copy fitting entails some counting. A page of 8 1/2 x 11 inches when placed on a draft, double space in Times New Roman, 12 points, would contain 250 words. If single space, that would be 500 words. So for a book of 144 pages (considering paper cuts), expect some 72,000 words.

But words are only words and they must be correct factually as well as grammatically in the way they are used in sentences. If we talk of allowed errors for a tenable confidence level, the margin of error for a book of 72,000 words should only be 7.2 where the errors are preferably found in typos.

Unforgivable

Therefore, 1,300 errors are not forgivable. It speaks more of ignorance than neglect. Even if Go found the errors to be 100 or 50, the number is still not acceptable.

The book had 2 consultants, 10 authors, 10 reviewers, 1 language editor, 5 members of the production team, 3 illustrators and 3 layout artists. But there’s nobody there at the top as editor in chief. Who could have acted as one? This is the key to the whole problem.

Michael L. Tan wrote (“Good Textbooks,” Inquirer, Jan. 10, 2015) that there was a lack of good textbook writers partly because the conditions were not encouraging. That is true. However, my experience regarding the most probable cause of sick books is not the same.

Publishing is more than just printing such that when people imagine themselves as editors and take charge of publications, they can do something disastrous. An example is placing one’s photo, big or small, in the work of someone. If you are an editor, your role is to support the work of the author. That is the theory.

Placing your photo there is diverting attention from the work of the author. Another one is explaining your role on one page as editor or part of an editorial team. There is no need, unless the author is dead. You are not making a foreword.

Stealing

Content-wise, a frequent practice of pseudoeditors is picking up images from the Internet, copyrighted or not, and including them in the book. And still another is translating materials from the original language into another and that becomes theirs already. That is stealing intellectual property plain and simple.

More important is the disregard for context. So we see Caucasian faces in materials for Filipino learners. In poetry, short stories and the like, we see the writings of foreigners. A good editor would notice the discrepancy.

There are those who do not know their place. They are not afraid of calling themselves editors and they are there doing publishing. They are more in the business of gaining something for themselves. You can easily spot such person based on his or her output.

First draft

When DepEd claimed that what Go had reviewed was the “first draft,” my suspicion that pseudoeditors were at work was all the more confirmed.

A real editor would not print—even just a few pieces for review—something that has a lot of errors. It would be a great waste of time, paper and ink. But mostly, his reputation as editor would be at stake. The purpose of a review is to spot errors that have slipped the notice of a proofreader after the editor is done.

So printing the book without considerable proofreading and review is costly, a very unwise decision. More so, when full editing is not done.

But the editor we are talking about is not someone merely assigned by virtue of a department order. He is one who went to school and has the knowledge, and if possible, is a graduate of journalism, communication and related sciences. He has experience and preferably a writer, too. A good editor would know more than those he is supervising.

For textbook writing, what is needed is a developmental editor (DE)—not a coordinator that has a doctorate degree but with very limited time to give. Not a printer, not a lackey. It has to be a developmental editor because, given a paucity of textbook writers, he can take charge of “writer-proofing” the supposed writers.

Like Ping-Pong

Writer-proofing is a process likened to Ping-Pong. The back-and-forth motion ensures that the material is suited to the needs of the target readership, is well written and is sufficient in scope.

In line with taking the bull by the horns, here are possibilities that could explain the 1,300 errors. There are two general situations and in the second one, there are three possible reasons.

Situation 1. There is no developmental editor involved in the work. A developmental editor looks at the big picture. He must have control over what happens to the whole book from planning to contents to artworks to printing. A book must have a developmental editor. He stays on top.

Situation 2. There is a developmental editor but:

He is not actually in charge. If he says there must be a layout of images every two pages, some artists do not follow. After the manuscripts are edited, they are whisked away to people who take over the work to have it printed.

He is not given enough time to work on the project. The work is bulky and needs the help of encoders-cum-clean copiers, fact checkers and proofreaders. But he doesn’t have enough time to do all these things before the deadline. All the same, nothing “in progress” should be exhibited outside the editorial office.

The process was not followed. Printing came first before any editing. Who would want to edit something already set in stone? Who decided that these manuscripts be cleared for layout? It should have been the editor’s call.

13 steps

A simplified correct process in developing a textbook is as follows:

Step 1: Writer writes the manuscript for an approved topic and checks if everything is all right before submitting.

Step 2: Editor edits.

Step 3: Encoder enters corrections.

Step 4: Clean copy is made.

Step 5: Proofreader reads.

Step 6: All clean copies are laid out for the book.

Step 7: Proof 1 (blueprint) is made for the editor.

Step 8: Encoder enters corrections.

Step 9: Proof 2 (blueprint) is made for the editor.

Step 10: To printing press (winner of bidding).

Step 11: Limited copies are printed for review.

Step 12: Enter corrections from review.

Step 13: Final print.

The steps are linear but can be repeated in the parts where there is writer-proofing. Also take note that in writer-proofing, much fact checking is being done so that by Step 11 very little change is expected. This means that agencies like science institutions can be consulted during the fact checking. The writer is expected to do her own research before submitting her work. It is not correct to be doing very little at the beginning and then reserve the end of publishing for macrochanges.

At best, the copies that have gone to the training of teachers on May 15 should have been the version that underwent Step 9. But with that number of errors, the obvious version can be said to have reached only part of Step 2.

Should we curse the likes of Go? We should be thankful that there are people like him who do not slumber when there are things to be checked.

Rebate people

A most important factor to consider here is the presence of “rebate people.” As practiced by most printing presses, 15 percent of the lot price, called rebate, is given to the one who can deliver the purchase order. This is the person who could rush the project since he is in a hurry to have his rebate. But take note of how technology has changed the configuration.

The environment for printing presses has changed with the advent of new printing technologies. In the 1970s up to the early 1990s, everything was done in printing presses from typing of manuscripts to artworks, and layout and finally to printing. There came a time that manuscripts could be placed in compact disks but some printing presses dreaded the day a virus would invade their shops.

They preferred to do everything, including the encoding. Work then depended on strippers (who cut negatives to paste them on a frame). Stripping took a lot of time and the editor has to sit beside him to guide him, the same way he has to sit beside the encoder cum layout man.

Camera-ready

These days, job orders are easier for the printing press. The editor simply arrives with a flash disk and there is no more need to encode, to layout, to provide artwork in the printing press. There is no more need to guide the strippers and do overtime in the printing press. Everything is camera-ready. The configuration has changed. More so with the rebate thing.

But you cannot do away with the editor. Without him, the work will be a disaster. A group standing as editorial staff won’t do—without an editor. For a printing press to take the role of an editor is a possibility—but then, only the mechanical side is accomplished.

Back to the sick book. Since the draft was shamefully exhibited in a national training program for teachers in a printed version, the editor clearly had no part in that exhibition. Only a proof can be exhibited outside the editorial office.

Probable explanation

Since it happened that way, chances are those who are running after their money had that printed. Why? To announce to all that the job order has already been awarded to a certain printing press and that no bidding is being welcomed anymore. The deal is closed. That is the most probable explanation. Especially so that books were coming from DepEd, volumes and volumes of just one book mean big money.

Owners of printing presses go after big colleges and universities, and big companies. Not only in bidding will they fight. They also advance to cancel others out—like going ahead to print drafts to the shame of the helpless editor.

Collusion

Shall we now have to watch collusion between owners of printing presses and DepEd officials? That appears to be the case but it is just like catching thieves and proving it is hardly our concern. What we can certainly do is to insist that textbook writing be overseen by a developmental editor.

We must insist that every element in textbook publishing is supportive of the objective of learning—beginning with the choice of editorial staff, the choice of contents, the writing and the development of the materials that must respond to good teaching practices.

We need people who put love in their work so that children after us can learn better.

(Jane Abao is a department supervisor of ADDPublications and an associate editor of SAGE Open, an international research journal. She can be reached at [email protected].)