Asean’s elusive integration

Leaders of the 10-member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations at a summit in Brunei. AFP

The University of the Philippines has shifted its school calendar from the June-May cycle to an August-July schedule. The main reason cited is the need to internationalize “as the country competes globally, but also in a region which will become an integrated Asean economic community by 2015.”

At the University of Santo Tomas, an approved school calendar shift also cites integration of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) in 2015 as a major rationale.

The premise of these moves is that Asean 2015 is a done deal and therefore one has to be ready or be left out of the regional initiative. A closer and more informed look at Asean, however, will easily disprove this predicate and reveal that regional economic integration remains an elusive goal.

Asean was established in 1967, but 25 years elapsed before the organization started integrating its member economies through the establishment of the Asean Free Trade Area (Afta) in 1992.

Nothing much happened and it took another 11 years before Asean leaders in 2003 resolved to establish an Asean Economic Community (AEC) as a single production base and market by 2020. In 2007, this date was advanced to 2015.

Drawn-out process

Asean integration has been a long and drawn-out process. But will the AEC finally come to fruition in 2015 as planned? A 2013 survey by the Economist of 147 big companies operating in the Asean region shows that only 6.3 percent were expecting that the AEC could be put in place by 2015.

The official statements issued at the end of the April 2013 and October 2013 Asean Summits in Brunei make no mention of achieving the AEC by 2015, only that the leaders “are pleased with its progress.”

Furthermore, the statements merely recognized the need to “intensify efforts in those areas under the AEC with high impact to ensure credible integration results by 2015.”

A 2013 study by the Asian Development Bank and Institute of Southeast Asian Studies cautions that: “Although the self-imposed deadline for the realization of the Asean Economic Community is 2015, it should not be viewed as a hard target. One should not expect 2015 to see Asean suddenly transformed, its nature and processes abruptly changed, its members’ interests substantially altered. Rather, 2015 should be viewed more as a milestone year—a measure of a work in progress—rather than as a hard target year.”

The study concludes that Asean “has no prospect of coming close to … (a) single market by the AEC’s 2015 deadline—or even by 2020 or 2025.”

There you have it. Governments, business leaders, journalists, research centers and financial institutions agree that Asean 2015 will not take place. Why has it been a long and tortuous effort for Asean economic integration to come about?

Problems of integration

Asean leaders’ AEC vision is weakened by a strong aversion for a diminished national sovereignty for the sake of deeper economic integration. National strategies clash with Asean’s internal goals. Several members refuse to lower tariffs on certain critical products. Malaysia insists on protecting its state-owned car and vehicle parts industries, fearing competition from Thailand.

Indonesia continues to protect its agricultural products while the Philippines refuses to open up its petrochemical products sector. Trade disputes still take place. In 2011 the Philippines filed a suit in the World Trade Organization against Thailand’s discriminatory taxes, duties and health measures against Philippine-made cigarettes.

Progress has been slow on eliminating nontariff barriers (NTBs).

Myrna Austria, a member of the faculty of De La Salle University, identifies these NTBs as “import bans, import subsidies, NTBs not elsewhere classified (such as nonautomatic import licensing, new procedures for importation, additional requirements for importation, etc.), quotas, sanitary and phytosanitary measures, and technical barriers to trade, state aid measures, public procurement requirements, trade finance, export taxes, and restrictions and investment measures.”

Impediments to the free flow of labor sour relations between Malaysia on the one hand, and Indonesia and the Philippines on the other, over the former’s treatment of migrant workers.

Intra-Asean trade woes

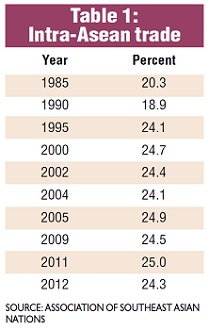

Despite the avowed goal of increasing trade among Asean economies, the record shows a virtually stagnant pattern. (See Table 1.)

Intra-Asean trade peaked in 1995 at 24.1 percent but since then, has barely moved forward with the average for 1995-2012 hitting less than 25 percent. Thus, for 17 years there has been scant progress in intra-regional trade.

Asean economies have been trading more with non-Asean economies than with themselves by a ratio of three to one. If, however, we consider that exports from Singapore (the region’s top trading nation) are mainly reexports, actual intra-Asean trade would even be lower.

Ranged against other long-running regional trading blocs, Asean’s record pales in comparison. The European Union has an intra-trade level of 67.3 percent while the North American Free Trade Association (Nafta) registers an intra-trade record of 48.7 percent.

The only major trade bloc with a worse record is Mercosur (Mercado Común del Sur), the South American alliance, with an intra-trade level of only 15.7 percent. The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation has only a 4.7-percent intra-trade level but its free trade agreement started only in 2006.

Not complementary

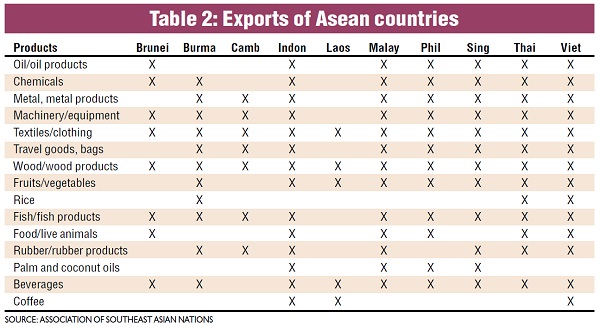

Asean economic cooperation has been a tough goal mainly because Asean economies are not complementary, i.e., they compete with each other.

As Table 2 shows, of 15 major Asean export commodities, it is only in rice, coffee and palm/coconut oils that three to four Asean countries trade in. The rest of the export product lines have more than half of Asean countries engaging in trading activities.

All Asean economies trade in wood and wood products and in textiles/clothing while nine of the 10 countries are in beverages, machinery/equipment, and fish and fish products. Eight Asean countries are engaged in exporting chemicals, metal and metal products, travel goods/bags, and fruits/vegetables. Seven Asean economies export oil and oil products while six are in the trading of food and live animals.

Under the Afta Agreement of the Common Effective Preferential Tariff (CEPT), average intra-Asean tariffs have been reduced from 4.43 percent in 2000 to only 1.06 percent in 2010. It is estimated, however, that only 5 percent of intra-Asean trade utilizes CEPT due to:

Existence of nontariff barriers

Bureaucratic procedures

High costs of applying for preferential rates

Minimal differences between CEPT and MFN (most favored nation) rates

High tariff countries’ reluctance to reduce revenues by promoting the CEPT, and

Lack of information on existence of CEPT

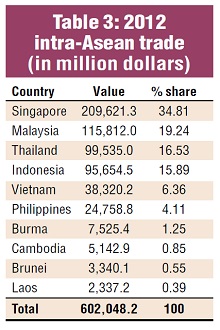

Looming over Asean are the vast inequalities associated with intra-Asean trade.

In 2012, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia dominated regional trade with an 86.47-percent share. (See Table 3.) Singapore alone had 34.81 percent. The bottom six countries (Vietnam, Philippines, Burma, Brunei, Laos and Cambodia) had only a 13.53-percent share.

Historically, Malaysia and Singapore have controlled regional trade, taking in two-thirds of total intra-Asean trade in previous years.

Challenges

Developments over the years have actually preempted and/or undermined collective efforts. Examples are the various bilateral agreements entered into by Asean member countries, such as between Singapore with Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Jordan, Panama, South Korea and the United States; Thailand with Australia, New Zealand, India and China; the Philippines with Japan; Malaysia with Japan; and, Indonesia with Japan.

As a body, Asean has also been moving away from integration by developing organizational linkages with non-Asean countries.

These include: Asean+3 (Japan, China and South Korea), the 2004 Asean-China Free Trade Area, the 2005 East Asia Summit, the 2005 Asean-Korea Free Trade Area, the 2008 Asean-Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership, the 2009 Asean-India Free Trade Area and the 2009 Asean-Australia-New Zealand Free Trade Area.

Currently being negotiated is an Asean-Hong Kong free trade agreement.

Also posing a challenge to Asean integration is China’s aggressive involvement in the Mekong subregion. As Geoffrey Wade, a fellow at National University of Singapore Asia Research Institute, pointed out, “heavy Chinese investments in dams, transportation routes, energy grids, trade bases and other infrastructure … weaken Asean and diminish its influence as a unified bloc.”

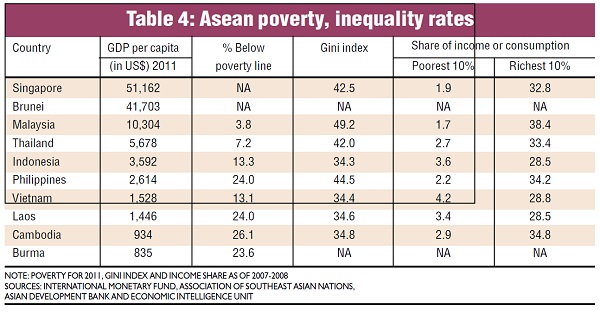

A specter haunting Asean’s path toward integration are the social inequalities within and between Asean countries. (See Table 4.)

Poverty levels

Poverty levels remain critical. In the Philippines, Cambodia, Burma and Laos, more than one-fifth of the population lives below the poverty line. While Singapore, Brunei, Malaysia and Thailand have zero or single-digit poverty indices, the remaining six continue to endure double-digit poverty levels.

Former Socioeconomic Planning Secretary Cielito Habito noted that “in 1970, of the five founders, the average income of the richest member country, Singapore, was 11 times that of the poorest, Indonesia; in 1990, this ratio was now 19 times; in 2000, 29 times.

In 2010, the gap narrowed to 14 times” but still worse than in 1990. He adds that “in 1990, of the 10 members, the richest, Brunei, was 201 times richer than the poorest, Burma. By 2000, Singapore, the richest, had 129 times Burma’s average income. The gap narrowed to 62 times in 2010, but was still worse than in 1970.”

Conflicting national strategies, similar export product lines, social and economic inequalities within and between Asean societies, and moves away from integration pose serious obstacles to realizing the AEC and reflect the absence of a distinct and unifying regional identity. Habito’s words are ominous.

After more than four decades of conscious efforts for greater integration of their economies, the five original Asean members—Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand—find their economies no closer to each other than they were when they first formally got together in 1967.

Finally, as the Economist observed, “Given the diversity of its 10-member economies, there is little that ties (Asean) together naturally.”

(Eduardo Climaco Tadem Ph.D., is professor of Asian Studies and editor in chief, Asian Studies [Journal of Critical Perspectives on Asia] at the University of the Philippines Diliman.)

Note: Poverty for 2011, Gini index and income share as of 2007-2008

Sources: International Monetary Fund, Association of Southeast Asian Nations, Asian Development Bank and Economic Intelligence Unit