China’s ‘cabbage strategy’ in West PH Sea

FILIPINOS stage a rally at the Chinese consular office in Makati City to support the “Global Day of Action” against China’s bullying and incursions in Philippine waters. NIÑO JESUS ORBETA

On February 18, 1932, Japan proclaimed the state of Manchukuo as the governing body for the region of Manchuria, which it had invaded and detached from China.

The date was a dark day in Chinese history that the people of China were determined to erase.

July 24, 2012 is a similar date in Philippine history, a blot in the history of the Filipino people that they are likewise determined to expunge.

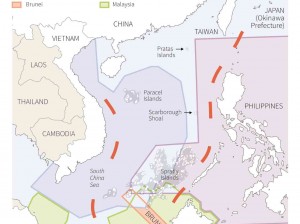

July 24 marked the first anniversary of the creation of “Sansha City” by the People’s Republic of China to “administer” the whole West Philippine Sea and the islands and terrestrial features that it claims belongs to China, among which are the Spratly Islands, the Paracels, Macclesfield Bank, Scarborough Shoal, Panganiban Reef and Recto Bank.

Cabbage strategy

Leading up to this dark day have been a series of provocative Chinese moves, including occupation of Scarborough Shoal or Bajo de Masinloc by up to 90 Chinese ships which have barred Filipino fishers from the area, an increased Chinese military presence at Ayungin Shoal and a Chinese general’s brazen presentation of the so-called “cabbage strategy.”

The thrust of the cabbage strategy, Major Gen. Zhang Zhaozhong explained, was to surround Bajo de Masinloc, Ayungin Shoal and other Philippine territories with a massive Chinese naval presence to starve Filbipino detachments and prevent reinforcements from reaching them.

What China adduces as a legal basis for its aggressive moves is a note verbale that Beijing submitted to the United Nations on May 7, 2009 which unilaterally asserted China’s “indisputable sovereignty” over all the islands in the West Philippine Sea and their “adjacent waters/relevant waters.”

Accompanying the note was the infamous “nine-dash-line” map. No official explanation for the nine-dash line was provided at that time or since, though there have been unofficial references to the islands and waters of West Philippine Sea being ancestral Chinese territories or to their inclusion in old maps of the defunct Nationalist Chinese regime that date back to the late 1940s.

Among the brazen claims of the nine-dash-line document is that the nine Spratly Islands and terrestrial features that have long been a municipality of Palawan belong to China. The Kalayaan Island group is about 370 kilometers from Palawan and some 1,609 km from China.

Another clear implication is that the Bajo de Masinloc, which is 137 km from the province of Zambales and is an integral part of it, also belongs to China, which is 700 km away.

Yet another assertion is that the Philippines and the other four other claimants to the West Philippine Sea are not entitled to their 200-nautical mile exclusive economic zones (EEZ) under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos) since the whole area falls under China’s “undisputable sovereignty.”

What most of the other claimants are left with are only the territorial waters that extend 12 nautical miles from their coast.

If allowed to stand, the nine-dash-line claim will probably be the most brazen maritime territorial grab in history.

Philippine position

In contrast to China, which is threatening to use force to enforce its claims, the Philippines has actively resorted to peaceful methods to resolve the territorial disagreements.

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) to which four of the claimants belong also favor a peaceful resolution, as shown by the declaration of the recent Asean Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Brunei, which reaffirmed the Southeast Asian governments’ “collective commitment under the [2002] Declaration of Conduct [of Parties] to ensuring the resolution of disputes by peaceful means in accordance with universally recognized principles of international law, including the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, without resorting to the threat or use of force, while exercising self-restraint in the conduct of activities.”

Also in contrast to China, which wants only bilateral talks in which it can bamboozle its much weaker neighbors, the Philippines has advocated and resorted to multilateral diplomacy to resolve territorial disagreements among several rival claimants. Again, Asean has supported this stance of the Philippine government.

With the exhaustion of all possible bilateral approaches to address the issue and to show its commitment to the use of peaceful methods to resolve its disagreements with China, the Philippines recently brought its case over Bajo de Masinloc to the United Nations for international arbitration.

The process would allow China, the Philippines and the other claimants to clarify their maritime entitlements under Unclos, paving the way for a truly peaceful and lasting settlement of the West Philippine Sea disputes.

The five-member United Nations Arbitral Tribunal formally began the hearing on the Philippine petition on July 11. China, however, refuses to participate in the process, a clear indication that it realizes that international law is not on its side.

Steadfastness matters

The Philippines’ and Asean’s moves have placed China on the defensive, making it realize that it is losing the battle for global public opinion by coming across as a regional bully.

Thus, at the Asean Foreign Ministers’ Declaration in Brunei Darussalam on June 30, it was announced that China had agreed to participate in talks to come up with a code of conduct to govern the behavior of the different claimants to the West Philippine Sea.

This was a step forward, but Filipinos are, like their government, cautious, waiting to see if Beijing is really serious about holding constructive talks.

The Chinese retreat showed the importance of being steadfast in defense of our national interests. But the significance of the Philippine stand goes beyond the Philippines, beyond the Asean countries that have claims in the area.

As Erlinda Basilio, the Philippine ambassador to Beijing, has stated, “the Philippines is not just protecting its national interest but fulfilling its international responsibilities in assuming its diplomatic stance.”

For what China is saying with its nine-dash-line claim is that a body of water that is 3,500,000 square kilometers, which borders six states and through which transits one third of the world’s shipping, is an inland or domestic waterway like Lake Michigan in the United States. Such a claim is simply unacceptable to all countries with a stake in freedom of navigation in the world’s seas and oceans.

Reproducing colonial behavior

China’s behavior in the West Philippine Sea dispute is a far cry from that of a state rectifying borders that were violated by colonial rule, like what the People’s Republic of China did in dismantling Manchukuo and reclaiming Manchuria after the Second World War.

It is that of a state that is behaving like a colonial or imperial state, imitating the expansionist conduct of the western powers and fascist-era Japan that it condemned in international fora.

Why is China behaving this way? Where is China coming from? There are two theories on the source of Chinese behavior. The first says it stems from insecurity. China’s increasingly aggressive rhetoric stems less from expansionist intent than from the insecurities brought about by high-speed growth followed by an economic crisis.

Long dependent for its legitimacy on delivering economic growth, domestic troubles related to the global financial crisis have left the Communist Party leadership groping for a new ideological justification, which it has found in virulent nationalism.

The second theory is that China’s moves reflect the cold calculation of a confidently rising power. It aims to stake a monopoly claim to the fishing and energy resources of the West Philippine Sea in its bid to become a regional and later, a global hegemon.

But whatever the source of its behavior, Beijing’s moves have alarmed its neighbors, and may be forcing them into the hands of the United States by allowing the latter to portray itself as a military savior or “balancer.”

If China feels threatened by the closer military relations the US is developing with its neighbors, it has, tragically, only itself to blame.

While many Filipinos have different opinions on the role of the United States, with some welcoming it as a savior and others seeing it as an opportunist taking advantage of the situation to project its might, most are united on the stand that military confrontation between the two superpowers is not the best way to resolve territorial disputes in the West Philippine Sea.

Regional leadership vs hegemony

Filipinos do not begrudge China for its effort to provide regional leadership. Indeed, many see it as a natural course of action for this hugely important country that is slated to soon become the world’s biggest economy.

There is, however, a great difference between seeking regional leadership and imposing regional hegemony. The sooner China behaves like a responsible regional leader and not like a power-hungry hegemon, the sooner stability will return in the area, the less opportunistic superpowers will be tempted to take advantage of conflicts among neighbors, the earlier China and its neighbors will finally achieve that mature relationship based on mutual respect for each other’s sovereign rights that was derailed by colonialism and the Cold War.

One nation united

The international community stands behind the Philippine government’s efforts to defend its interests in the West Philippine Sea.

One of its strongest sources of support is the Filipino nation. Standing squarely behind the government are not only the people living in the Philippines but also those in the global diaspora.

From Manila to Riyadh, from Rome to New York, 12 million global Filipinos are asserting that the Philippines will not be bullied into submission.

On July 24, Filipinos held protest rallies in key cities all over the world to bring the weight of global condemnation to bear on China to make it rethink the costs of its aggression toward the Philippines.

(Loida Nicolas-Lewis is the chair of the Global Filipino Diaspora Council, of which Rodel Rodis is the president. Walden Bello is a representative of the Akbayan party-list group in the Philippine Congress.)

For comprehensive coverage, in-depth analysis, visit our special page for West Philippine Sea updates. Stay informed with articles, videos, and expert opinions.